I Believe in God: Ode to Joy

Luke 1:26-56

December 13, 2020

Emmanuel Baptist Church; Rev. Kathy Donley

A recording of the worship service in which this sermon was preached may be found here: https://youtu.be/LGVr7omMaCQ

Mary was perplexed. More perplexed than fearful, it seems, at least at first, at the angel’s announcement. That’s what Luke says. But I think stunned might be better. Or astonished, dumb-founded, gob-smacked.

It just doesn’t really make sense. She has done all the right things. Her parents are respectable. She is respectable. She is betrothed to Joseph who is honorable. How can this be happening?

But then as the implications begin to sink in, she understands why the angel began, as they always do, with “do not be afraid.” She imagines what her mother will say, what Joseph will think, and she is terrified. She is about to leave her parents’ home to go to Joseph’s home, which was frightening enough, but now this. Will she survive the scandal? Will she survive child-birth?

Despite the questions flooding her being, to Gabriel, she says “Let it be.” To God’s messenger, she says “yes.” This story is so familiar that it no longer astounds us. We see Mary as merely obedient, just doing what is required of her. But we should recognize her courage. We should applaud her heroism.

Mary’s yes to Gabriel is very costly. She says yes to a scandalous pregnancy, to the possibility of death by stoning or in childbirth. But the cost will not end when she delivers a healthy baby and lays him in a feeding trough. When her son grows up, people will say that he is out of his mind, possessed by the devil. They will call him a trouble-maker, a drunkard, someone who hangs with the wrong crowd. He will suffer torture and death which Mary will have to watch and be helpless to prevent.

Writing from prison before his execution by the Nazis, Dietrich Bonhoeffer said, “There remains an experience of incomparable value. We have for once learnt to see the great events of history from below, from the perspective of the outcast, the suspects, the maltreated, the powerless . . . – in short, from the perspective of those who suffer.” [1] The story of Mary and of Jesus can teach us to see history from below.

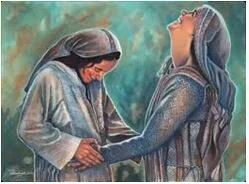

She is courageous, but she needs support, which she seeks by taking the journey to see Elizabeth, her older relative. Perhaps that is what Gabriel has in mind by telling her that Elizabeth is also pregnant.

“Two women in a land under brutal occupation learn that they are pregnant. One is unmarried and knows that bearing a child will expose her to rejection and judgement, perhaps even violence, from her community. The other has been childless for years, and has probably been shamed and scorned because of it. Though this child will be welcome nothing can wipe out those years of anguish. And neither child will survive long enough to care for their parents in old age, in any case. Both will have been brutally executed by their mid-thirties, victims of the political and religious suspicions and hatreds of their time. . . . In Luke’s Gospel, Jesus is born amidst the chaos of a Roman census, a forced mass migration demanded by Caesar with no apparent thought of the human cost involved. He is telling us that this will be a story set in a world where rulers with great power do what they want and the ‘little people’ just don’t matter.”[2]

You know that way back in March, I was in Matamoros, Mexico. I showed you pictures of the migrant camp there, the site of another mass migration, this one forced by poverty and violence. It is a place inhabited by those with little power and little value in the eyes of the authorities. In October, a baby was born there. I expect that many babies have been born there, but I heard about this one. Consuela, an asylum-seeker from Guatemala, went into labor very quickly. The baby came so fast that there was no time to get her to a hospital. She gave birth near the river, tended by other women in the camp. The baby was born so quickly that she hit her head, but reports were that she was fine. I think about Consuela and her baby and I wonder at her courage. I wonder kind of future she dares to dream of for her child. If I were in her place, I would not get my hopes very high.

But Mary did, and Elisabeth too. They believed that the children they carried would bring a new future. Elisabeth pronounces Mary blessed which was just the kind of encouragement she needed to break into song.

Her song is called the Magnificat because that’s the first word of it in Latin. “My soul magnifies the Lord” she says.

Mary sings. I wonder if she danced too. There’s a video circulating in cyberspace right now of a young girl dancing. She is about 4 years old. She is standing on a couch which is backed up to a picture window. She is watching out the window for the letter carrier. This is the routine that has developed for the last several months. Every day, she watches for the mailman. Every day, as he walks up the sidewalk, she dances. And he does too. In the video that has gone viral, you can see him through the picture window. He carries the mail to her front porch and dances while he does it. He goes back out the same way, dancing. He imitates her moves and she imitates his. And the neighbors look on and laugh. This very small thing has become a daily source of joy for the whole street.[3] I wonder what we don’t see. I wonder what the mailman struggles with personally, what stresses he is carrying. I wonder if some days, it takes a bit of courage to dance with this child.

Mary sang and maybe she danced too. She was joyfully courageous, with her song of yearning and hope and peace and justice. She sings of a God who enters our world from below, of one who does not accept the world’s power arrangements. This is a song of revolution on the lips of a peasant girl. If it wasn’t so familiar to us, it might astound us.

When Martin Luther translated the Bible into German, he left Mary’s song in Latin. The German princes who support and protected Luther in his struggles took a dim view of the social and political implications of the Magnificat, with its reversal of social structures. Not wanting to lose his friends in high places, Luther thought it best just to leave the Magnificat in Latin.[4]

But those with less power, the outcasts, those who suffer, have continued to read it anyway. Ernesto Cardenal recorded Bible studies held within a community of campesinos, farmers and fisherfolk who lived around Lake Nicaragua in the 1970’s. As they read Mary’s song, one said, “It’s not the rich, but the poor who need liberation.” Another answered “The rich and the poor will be liberated. Us poor people are going to be liberated from the rich. The rich are going to be liberated from themselves, that is from their wealth. Because they’re more slaves than we are.”[5]

What Mary imagines, what she trusts God for, is the liberation of everyone, the setting free from sin and bondage and despair.

I have told you before about my seminary professor who was in Berlin in 1989 when the wall came down. He described for us the peaceful protests that led up to that event. For several months, people gathered around the St. Nikolai church in Leipzig. This is a place where Bach composed so many of his cantatas, like the sample we heard from the choir today. The people gathered to pray and sing at St. Nikolai church, more and more each week, until the day when they numbered more than 70,000 people. They spilled out into the streets with their prayers and candles, singing songs of hope and protest until their singing shook the powers of their nation and the authorities did not know how to respond.

One American pastor who visited a few months after the fall of the wall asked why this movement had not been crushed like so many before it. The answer came that the police had no contingency plan for song and prayer, no counter-measures against praying and singing.

We might think that song and prayer are too small for the weight of the worries we carry, insignificant against the fear and stress and even hostility we may be facing. We might think that the few of us who come together to sing and pray each week are a small thing in the face of the worries we carry, the fear and stress we are all bearing right now. Or we might join Mary’s song.

It's a song that has been sung for generations. It was and still is heard when the monastics sing Ubi Caritas -- where love is, there is God.

It’s heard every summer when campers gather around the bonfire and sing Kum Ba Yah. And when children or protesters sing This Little Light of Mine.

When they sang Verdi’s Requiem in the concentration camp, or Ode to Joy in Chile during the Pinochet dictatorship, when Sweet Honey in the Rock sings “We who believe in freedom cannot rest until it comes” -- that’s Mary’s song to a different tune.

When Christians sing Joy to the World every Christmas, we’re singing Mary’s song all over again.

Each successive generation must find its tune in their own time. Including us– we also must find the way to sing this song, to know that God is begotten in us. It is the melody of faith rising yet again, offering defiant and courageous hope to a weary world. Thanks be to God. Amen.

[1] Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Letters and Papers from Prison, (New York: Touchstone, 1953) p. 17

[2] The Rev Anne LeBas in her sermon “The Power of One” http://sealpeterandpaulsermons.blogspot.com/2012/12/advent-4-power-of-one.html

[3] https://youtu.be/RTWA3GN3od8

[4] John Buchanan, “Revolutionary Words” The Christian Century, December 12, 2012

[5]Quoted by Kimberly Bracken Long in Feasting on the Word, Year B, Volume 1, David Bartlett and Barbara Brown Taylor, general editors, (Louisville: Westminster/John Knox Press, 2008) p. 95.