The Great Multitude

Revelation, 7:9-17

November 1, 2020

Emmanuel Baptist Church; Rev. Kathy Donley

A recording of the worship service in which this sermon was preached may be found here https://youtu.be/L4FkWqYEU5o

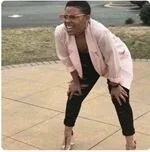

This meme has been trending. It is of a woman leaning over with her hands on her knees, squinting far down the road. The caption reads “Me looking outside to see what chapter of Revelation we’re doing today.” In a year that has brought pandemic, hurricanes, wildfires, murder hornets, durecho storms, political and economic turmoil, this kind of humor seems appropriate. We might as well look down the road to see which horseman of the apocalypse is headed our way today. We associate the book of Revelation with bizarre symbols and cataclysmic events, but it is not unlike some of the ways that 2020 is being described.

John was a follower of Jesus in exile. Sent to the island of Patmos, living in a cave thirty-seven miles from the mainland, he was isolated from his faith community -- a community struggling to hold on in the midst of great difficulty. The vision which we have in the book of Revelation was John’s gift to them, a vision in which he proclaimed that the world will not always be the way it is now, and that the power at the center of the universe is the power of love.

Here in chapter seven, that power belongs to the Jesus the Lamb, the one who has conquered not with violence, but with love. Jesus the Lamb whose vulnerability and sacrifice was ferocious and powerful and victorious. This is the enduring power at the center of the universe, the power that has and will change our world.

John’s vision is of a great multitude who have come through an ordeal. He describes it for people who are living in the midst of an ordeal and for every generation since then. The multitude is more than can be counted – people from every tribe and ethnic group, every language and race, before the throne of God. It is a vision of what is happening now on a plane we cannot yet perceive and a vision of the future when the redemption of the world is complete.

On All Saints Day, we imagine all those who have lived before us, all of those who died in God’s love and perhaps we can try to imagine the size of the multitude, extending in every direction as far as we can see, more than we can count. But also, we imagine smaller groups within that crowd, people we know and love, people who left us more recently, whose lives continue to shape ours.

My Uncle Eddie died in March. Since then, his children, my cousins, have been dealing with the house and farm that he and my Aunt Joyce left behind. They have shared pictures with my generation of treasures they’ve found in the attic, things from their childhood and antiques like quilts and silver and documents left by their parents’ parents. The farm, where my Aunt and Uncle lived for decades, is now on the market. A week ago, I saw the realtor’s listing. It’s a very simple house. It still has the furniture that I remember. It is undoubtedly full of all kinds of memories for my cousins who grew up there. Aunt Joyce and Uncle Eddie lived on the farm next to my grandparents, so for me the pictures conjure up a line of Thanksgivings spent with the Donley clan. I imagine that when we join that great multitude, we are each going to be looking for those who were part of our holiday celebrations.

There are a lot of fascinating stories about Christians through the ages. There were people called anchorites who lived in cells, spending their lives in tiny rooms praying and reading Scripture. There were hermits who went to the desert or lonely mountain cabins to devote themselves to God. One young boy read about a man who lived for 30 years on top of a 60-foot pillar in Syria. The boy decided that he was called to perform a similar act of heroism, so he went into the kitchen, climbed up on top of the kitchen cabinet and stayed there all morning. At lunchtime, he came down. His mother, said, “Now you must not feel bad about this. You have at least made the attempt, which is more than most people have ever done. But you must remember that it is almost impossible to be a saint in your own kitchen.”

It is almost impossible to be a saint in your own kitchen. Maybe so. But in our own kitchens and neighborhoods, with our family and friends, that is where we are most often called to be saints. Of course I am using saint the way that is it used in the New Testament – where it means a person who has been made holy by Christ. It means every Christian not just the ones we remember for particular acts of courage or piety.

We usually learn more about the power of love from those who are closest to us. Which is why that the list of names we lifted up today included people we knew personally. You sent me the names of parents and family members and people from Emmanuel with whom you worshipped and argued and shared jokes and potlucks. It included Mark’s mentor in chaplaincy and my ethics professor, people who shaped us directly. Pat asked us to remember May Shane. Mrs. Shane was Pat’s Sunday School teacher at Calvary Baptist Church in Charleston, West Virginia when Pat was a senior in high school. Pat says that she was marvelous and influenced her so much at a pivotal time in her life. You and I don’t know May Shane. But we know Pat and we know how many other lives she has influenced since she was in high school. That is part of the mystery we stand before today – that enduring power of love in which we are conformed to the image of Christ is often conveyed to us by those who are saints in their own kitchens or workplaces or churches.

It is personal and close, but also big and beyond our understanding. Ann and Adoniram Judson were also on our list. They went to Burma 200 years ago. Our connection to them would seem to be mostly historical. Except that they shared Christ’s love with the ancestors of the Karen and Kachin people who moved to Albany. People whom we had the opportunity to welcome and support and to share faith with in this time and space.

A friend went to vote this week. In line, standing 6 feet apart, at her election site, she said there was good-natured conversation and some humor, a feeling of togetherness. She was trying to describe how unexpectedly good this experience had been. She said that she had the sense that there were others present, people who had sacrificed greatly to make it possible for her to vote, for everyone to vote. She said that she felt like they were there, unseen, the great multitude who had gone on before. And as she was describing it, it surprised both of us when her voice broke and the tears came.

We remember those who shaped us, those who inspired us, those who endured before us, those we knew personally and those whose names we may never know. When that remembering comes with tears, they are a testament to the mystery and the power of Christ’s enduring love.

After his mother died, the late Henri Nouwen wrote a book called Our Greatest Gift, in which he said this:

“When we can reach beyond our fears to the One who loves us with a love that was there before we were born and will be there after we die; then oppression, persecution, even death will be unable to take our freedom. Once we have come to the deep inner knowledge—a knowledge more of heart than of mind—that we are born out of love and will die into love, that this love is our true Mother and Father, then all forms of evil, illness, and death lose their final power over us.”[1]

Nouwen got a glimpse of that reality described by John of Patmos. And so have others. Desmond Tutu was Bishop in Johannesburg, South Africa in the 1980’s, during the ordeal of apartheid. He described his experience at St. Mary’s Cathedral there like this:

“There is no question whatever that our Cathedral is thoroughly prayed in by all kinds of people – black people, white people, big people, little people, representatives of the variegated family of God find a warm welcome . . .I will always have a lump in my throat when I think of the children at St. Mary’s, pointers to what can be if our society would become sane and normal. Here were children of all races playing, praying, learning and even fighting together, almost uniquely in South Africa. And as I have knelt in the Dean’s stall at the superb High Mass with incense, bells and everything, watching a multi-racial crowd file up to the altar rails to receive communion, the one bread and the one cup given by a mixed team of clergy and lay ministers, with a multi-racial choir,– all this in apartheid-mad South Africa – then tears sometimes streamed down my cheeks, tears of joy that it could be that indeed Jesus Christ had broken down the wall of partition and here were the first fruits of the eschatological community right in front of my eyes, enacting the message in several languages on the noticeboard outside that this is a house of prayer for people of all races who are welcome at all times. St. Mary’s had made me believe the vision of St. John “After this I looked and saw a vast throng, which no one could count, from every nation, of all tribes, peoples and languages standing in front of the throne . . .” [2]

When we can reach beyond our fears to the One who loves us with a love that was there before we were born and will be there after we die; then oppression, persecution, even death will be unable to take our freedom.

Thanks be to God. Amen.

[1] Henri Nouwen, Our Greatest Gift: A Meditation on Dying and Caring (New York: HarperCollins, 1994), pp 16-17.

[2] Desmond Tutu, Suffering and Hope, (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1984) 134-136.