Testify to Love: Under Construction

Luke 3:1-6, Philippians 1:3-11

December 9, 2018

Emmanuel Baptist Church; Rev. Kathy Donley

A voice crying in the wilderness. . . You might associate that expression with John the Baptist. He shows up regularly in this season of Advent. In modern usage, “a voice crying in the wilderness” means a voice that no one is paying attention to or an unpopular voice. But that is not Luke’s reference. Luke is quoting Isaiah. Isaiah was describing a marvelous highway, a smooth road that would lead the people of Israel home from exile. The wilderness image reminds people of coming home from captivity. The wilderness is also the place where the people of Israel were first formed by God, as they wandered there with Moses after the Exodus. John the Baptist’s message is not one that is going unheeded. In fact, Luke tells us that crowds of people are going out to hear him. John proclaims hope; he announces the opening of the way to freedom and salvation.

Luke situates John in a specific moment in Israel’s history. It is possible to date all the Roman officials he names, except Lysanias, whose name was shared by several rulers. On this basis, we can tell that Luke is placing the preaching of John the Baptist in the years 28-29 CE.[1] God is doing something big and new, something that is part of God’s overarching purpose, something that transcends human concepts of space and time, but is also somehow connected to a specific place and point in human history. Luke names the Roman rulers who are impinging on Israel. He also names the religious leadership of Annas and Caiaphas which is inevitably compromised by the occupation.[2]

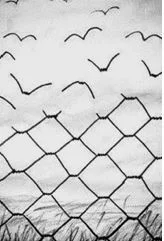

The people are pouring out into the wilderness, because they want a word of hope. They go out into the wild, unfamiliar place in order to hear how to go home spiritually. They are experiencing a kind of exile-in-place. They live in their home country, but it is occupied by a foreign power. Their religious authorities, co-opted by the political ones, are not offering any meaningful answers. So they go out into the wilderness, far from the likes ofTiberius and Herod and Pilate, far from Caiaphus and Annas, to learn from John. John is wild and bold. He is not playing by the rules, not working within the system, but outside it. It is not a stretch to call him “unfettered.”

Isaiah spoke of a return from exile in a foreign land. John the Baptist calls people to return from the exile of a religion that has lost the love of God and human beings at its center. Please hear me carefully. I generally refrain from criticzing first century Judaism. There is much we cannot know about it, separated as we are by time and space. And as a church leader myself, I know how easy it is to be critical of other people and how hard it is to refor ourselves. In this case, I am trying to describe John’s own critique from within first century Judaism. And I also think it is instructive for us in our own context. Much has been said about younger generations absenting themselves from church. It’s a concern for many of us, and I have to wonder if some of them are going out to a wilderness looking for answers that churches are failing to provide.

Brian McLaren is a theologian and activist familiar to many of us. In a recent interview, he talked about the ways the church needs to be transformed. He said that the younger generations’ rejection of church is a message we should be paying attention to. He said, “What has happened to a lot of us is we have ended up with a checklist mentality. There are all these things we have to do because that’s what we think we have to do. On Sunday morning we have a liturgical checklist. In the course of a year we have certain events. Every once in a while, we have to go back and say, why are we doing these things? Are they furthering a grand sense of mission? When we realize that, I feel it’s necessary to go back and say what are we here for and align everything we do around that fresh sense of mission. For example, if our job is to produce people who love God and love their neighbors as themselves and the earth, then immediately we would say we are not doing a very good job of that. . . . I had to admit as a pastor I met a lot of people who had a lot of pew time and knew a lot of Bible lore. But the more they knew they just became more arrogant and critical and they weren’t becoming more loving, and that raises real questions about the value of what we are doing.”[3]

I agree with Brian. These are the very questions we need to be asking,especially as we adopt a budget for our next year of ministry, especially as we live into the change of a new governance structure. These are conversations we are having and will continue to have in the next weeks and months.

But in this moment, we are also here to testify to love. So let us turn our attention to the letter to the Philippians. Paul is writing to a group of people who have embraced an adventure in faith. They are the pioneers, the ones who have heard the gospel and are living it out. Again, we hear that God is doing something big and new.

Paul writes, “I am confident of this, that the one who began a good work among you will bring it to completion by the day of Christ Jesus.”

This work began at creation and will be complete in the day of Christ Jesus. There is an overarching purpose, something that transcends human concepts of space and time, but again we see specific people in a specific location are part of the divine drama.

“Notice that Paul takes no credit, neither does he give credit to his friends for the progress that has already been made. They are engaged in a massive construction project, but it is not a project they originated. Rather it is God’s idea—the renewal and reconciliation of the world. God started this project. God will finish it. There will be no darkness unvanquished, no buildings unbuilt, no conflict unresolved, no death unanswered by life when God gets through.” [4]

In verse 9, Paul says, “this is my prayer, that your love may overflow more and more with knowledge and insight . . .” Writing to a fledging church, a congregation just beginning to shape their lives together, his prayer is that their love may overflow more and more. I think of Jesus’ words in his sermon on the plain. He said, “Give and it will be given to you. A good measure, pressed down, shaken together, running over. . .” That is how I imagine unfettered love – as much you can press into a container, then shake it down and add more, and it will keep spilling out the top.

This is widely considered Paul’s most joyful letter to his favorite church. It is also a letter written from prison. Paul was bodily chained to his guard. There were no concerns for his civil rights. He couldn’t even expect to be fed unless he or one of his friends supplied money for his food. It is under those conditions that he writes this most joyful letter about overflowing love. In spite of his captivity, Paul’s love is unfettered.

Paul invites the Phillippians to see their lives as under construction, with the major building material being love. He describes this love as containing knowledge and insight. In the adult Sunday School class last week, one of you described love as that which helped you notice things. Apathy and concern for our own needs can keep us from attending to the needs of others, but as we grow in love, we become aware of things we never saw before. And as our awareness grows, love overflows and leads us to respond. Our love is constructed within certain parameters – we love certain people in certain situations within the confines of what is considered acceptable. But as we allow God’s love and God’s purposes to work in us, that love abounds and overflows and over-runs those parameters.

The Rev. Traci Blackmon is now the Executive Minister of Justice and Witness Ministries for the United Church of Christ. In 1985, she was a registered nurse in Birmingham, Alabama.

Arriving for the evening shift, she was told that there was an “AIDS patient” on the unit. The staff said that he was mean and belligerent. He was spitting at nurses and trying to infect them. They said he was so mean that not even his family had visited him.

This was in the early days of HIV/AIDS when not much was understood about the disease. The staff was afraid of it and of this patient whose name was James Bell.

Like her staff, Traci was afraid, but she was the charge nurse. So, at the start of shift, she went to James’ room to introduce herself. There was full isolation wear outside his room, but even though she was afraid, she said “the spirit told me not to gown on my initial rounds.”

She opened the door to his room and could not believe her eyes. There were disposable trays of food stacked up on various surfaces. The trash cans were overflowing. It was obvious his room had not been tended to in at least a couple of days. She called for cleaning but no one would come.

She walked to his bedside. He stared at her. She wondered if he would spit at her. She put her hand on his arm and told him her name. She said that she would provide his care that night. She said, “His eyes never left mine. And then I saw them. The tears began to fall. I asked if I was hurting him. Was he in pain? He told me no. “

“It turns out that I was the first person to touch him skin to skin (no gloves) since he had been admitted a few days before. The mere human touch caused him to weep. I spent a great deal of time with James that night.”

“I cleaned his room. Bathed his body. Emptied his catheter. Changed his sheets. And while I cared for him...he told me that his family disowned him when they found out he had AIDS. His closest friends were dead or dying. And he felt all alone. I charted in James’ room that night instead of at the desk. He seemed to have a lot to say...and no one else was listening. So I wanted to stay close.”

“I’m glad I did. By the time I returned the next night. James was dead. I am still haunted by the way James was treated in our care. And though I couldn’t do much...I will forever be grateful for that human touch and the time we shared that night. Education is necessary. Treatment is necessary. But there is a wounding that happens in isolation that only love can heal.”[5]

Unfettered love. Love that knowingly disregards the rules, the concern for personal safety, in order to offer care. Love stronger than fear. Love that overcome fears. Love that notices the pain of another. Love that overflows with insight and knowledge and healing.

I hold onto these memorable words from Dr. King. “Returning hate for hate multiplies hate, adding deeper darkness to a night already devoid of stars. Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate, only love can do that.”[6]

Paul says that this overflowing, unfettered love produces a harvest of righteousness. Last week, we said that righteousness is the right ordering of the world in ways that allow life to flourish. Righteous love keeps us alive in this world. Unfettered love casts out fear. Overflowing love drives out hate.

Sisters and brothers, love is our greatest strength, our super power. And this my prayer, that our love may overflow more and more with knowledge and full insight, until God who began a good work in us brings it to completion in the day of Christ Jesus. Amen.

[1] Justo Gonzalez, Luke in the Belief Commentary Series, (Louisville: Westminster/John Knox Press, 2010), p. 48

[2] Wes Avram in Feasting on the Gospels, Luke, Volume1, Cynthia Jarvis and E. Elizabeth Johnson, editors, (Louisville: Westminster/John Knox Press, 2014), p. 65.

[3] https://baptistnews.com/article/increasing-rejection-of-church-a-good-thing-brian-mclaren-says/#.XAx9wHRKiUl

[4] The Rev. Joanna Adams in her sermon “Under Construction” http://www.fourthchurch.org/sermons/2003/120703.html

[5] As told by the Rev. Traci Blackmon, https://www.facebook.com/traci.blackmon?lst=100001539525578%3A1274314586%3A1544311499

[6] Martin Luther King Jr, Strength to Love (New York: Harper and Row, 1963), p. 47.